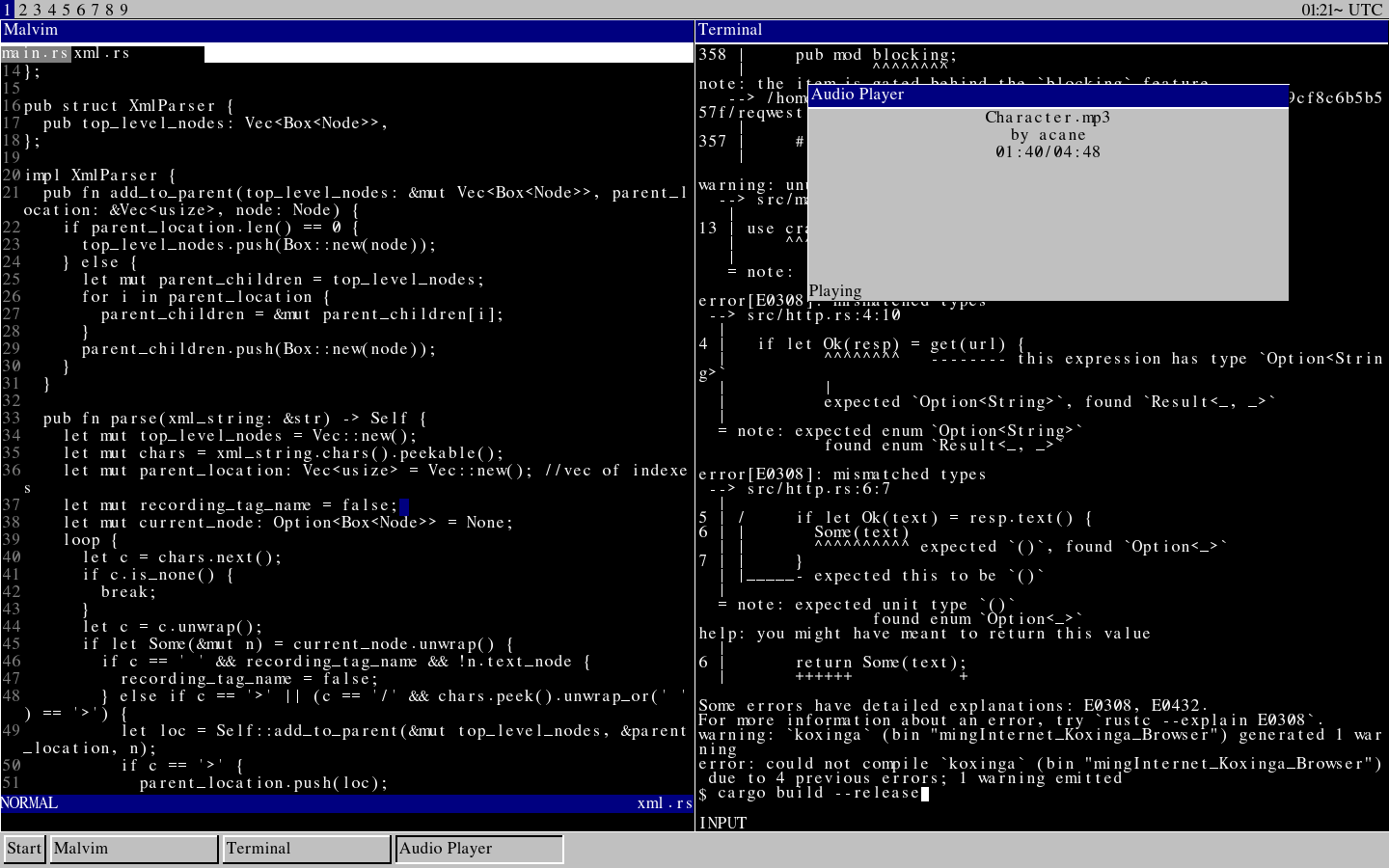

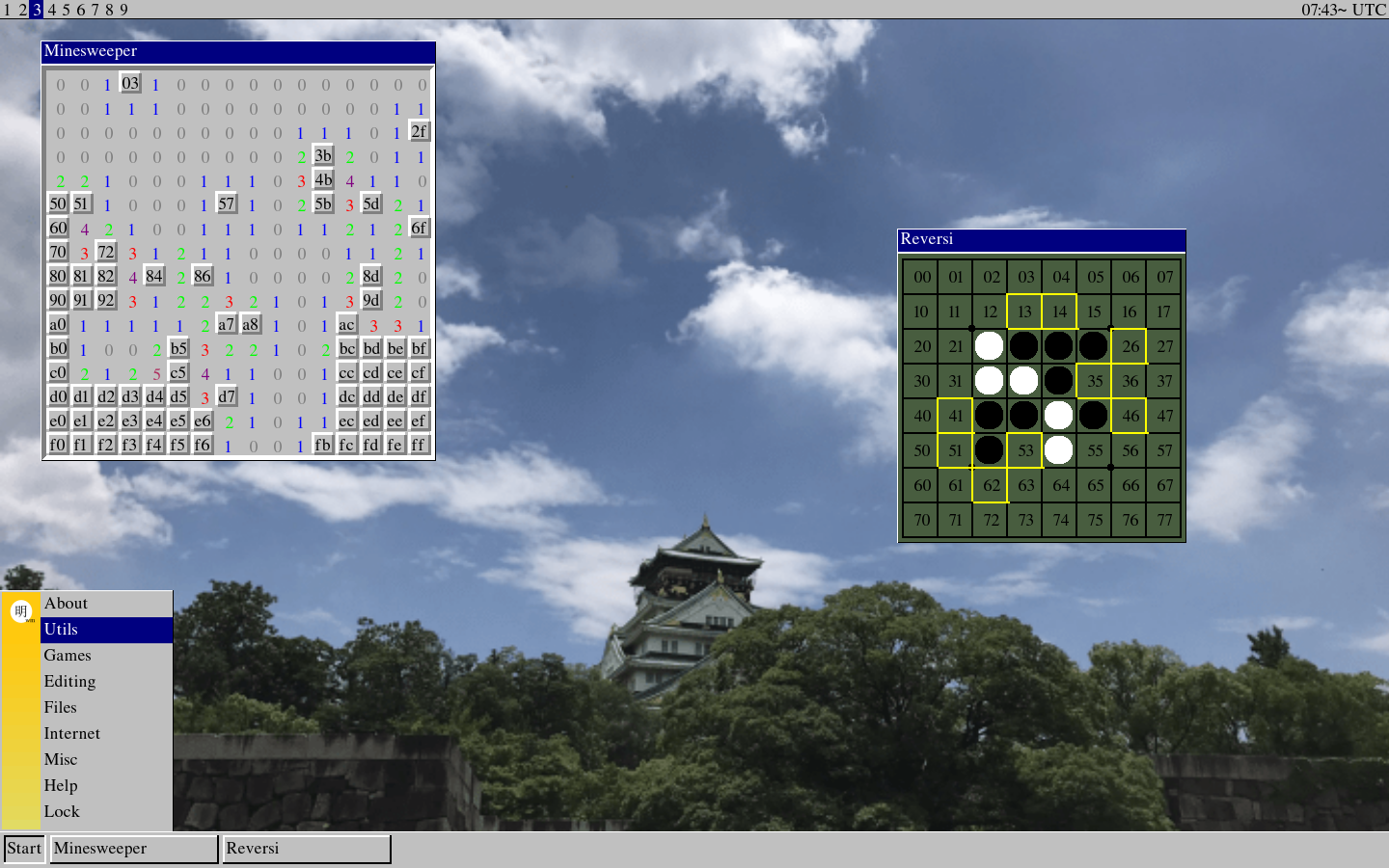

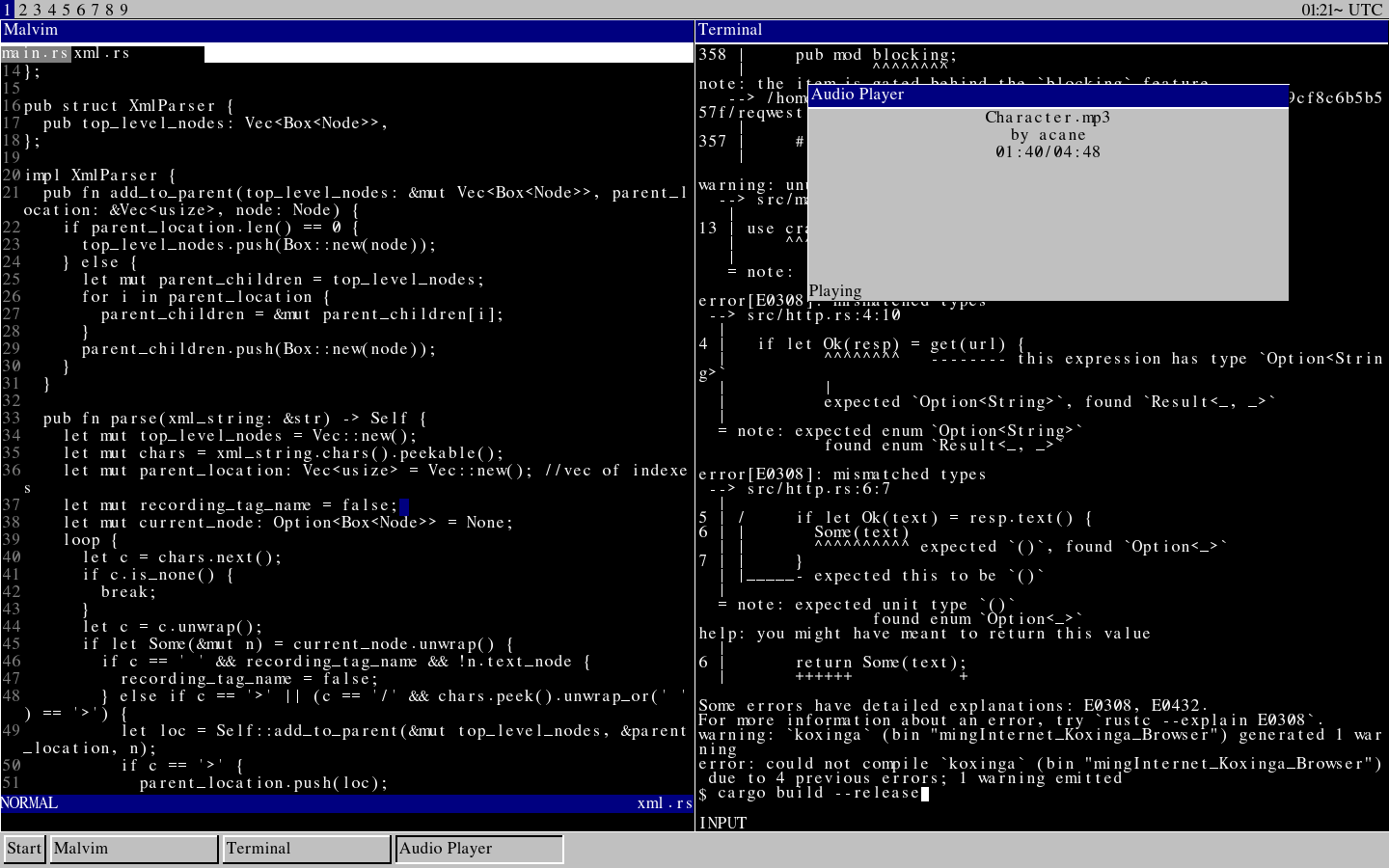

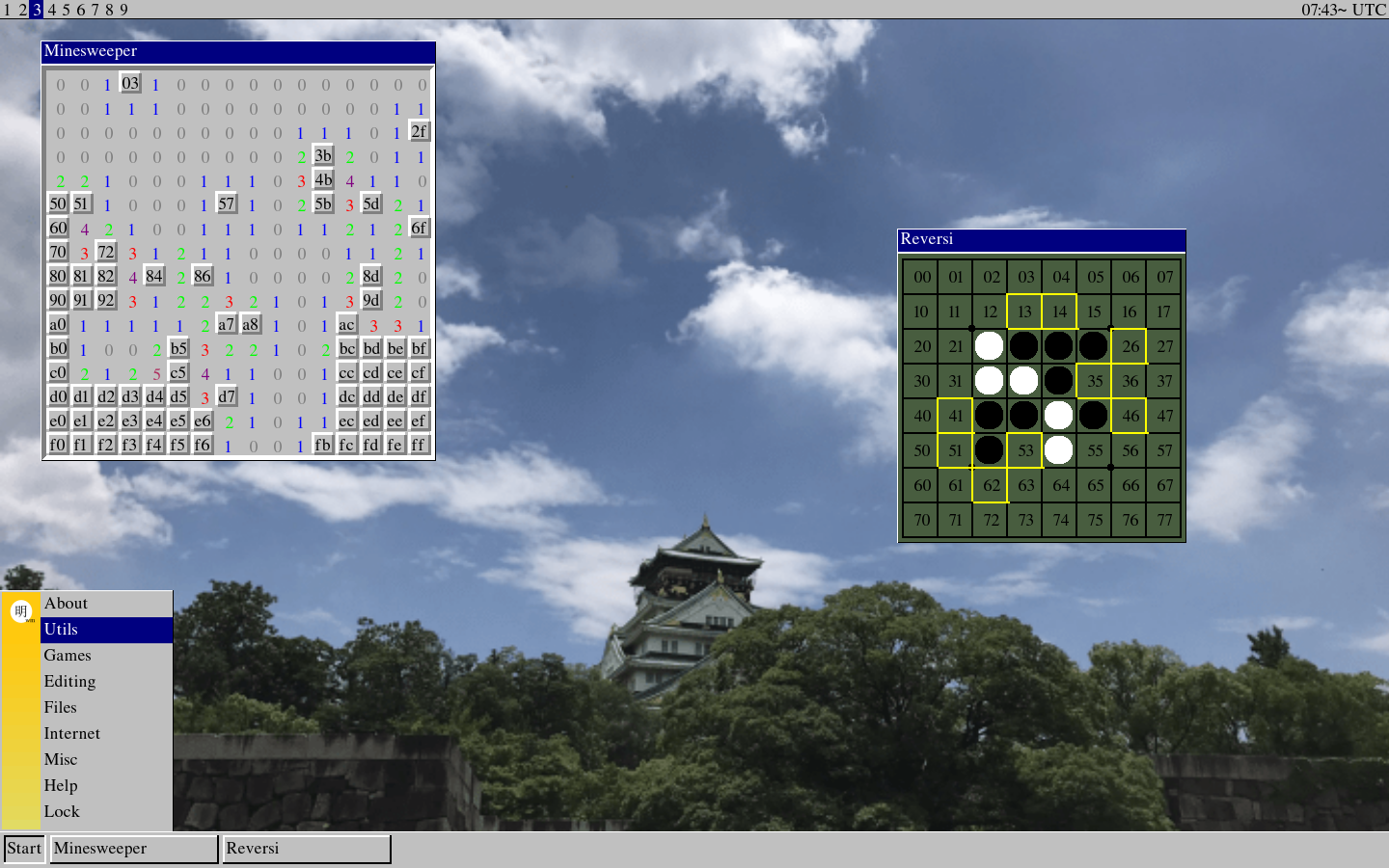

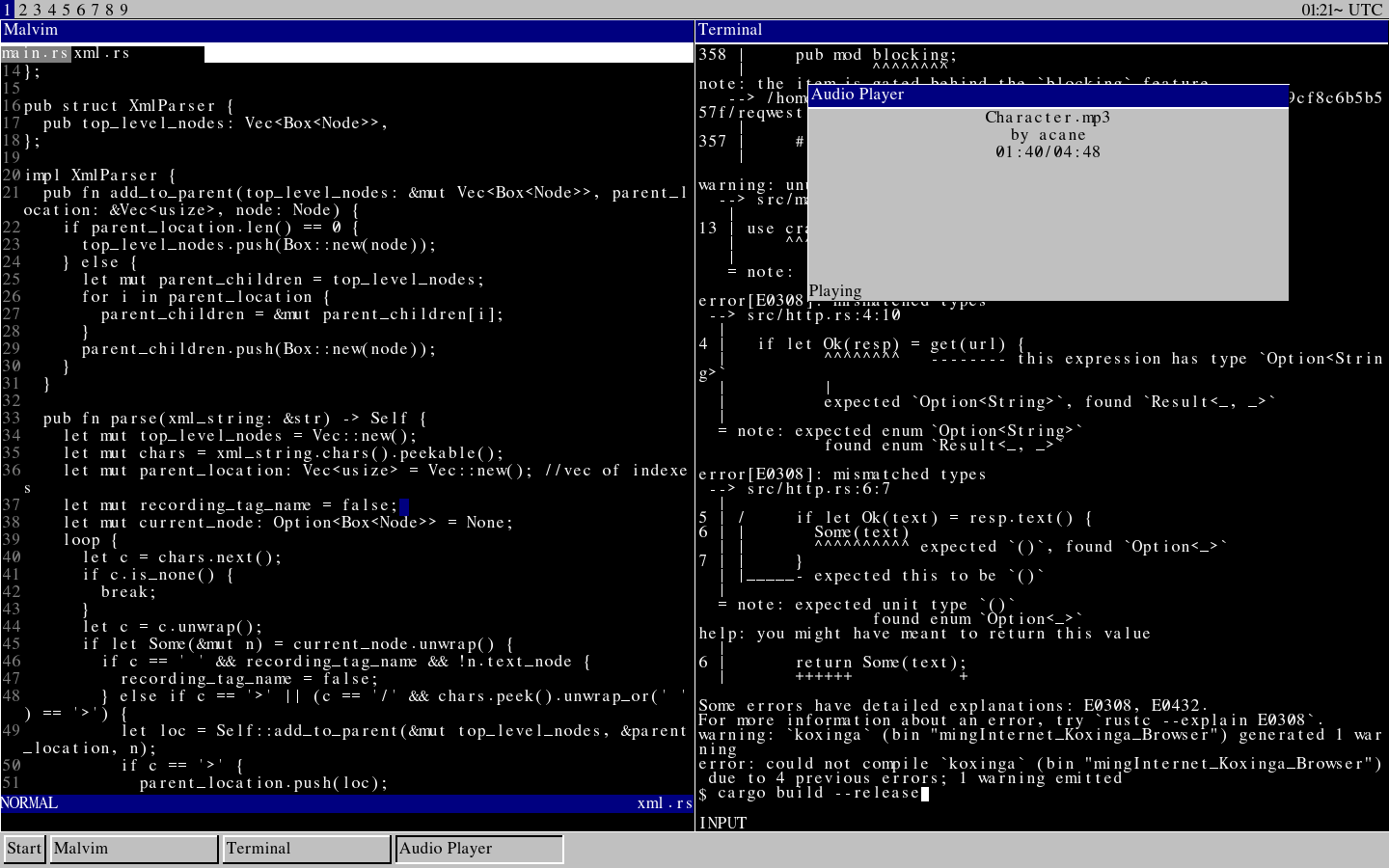

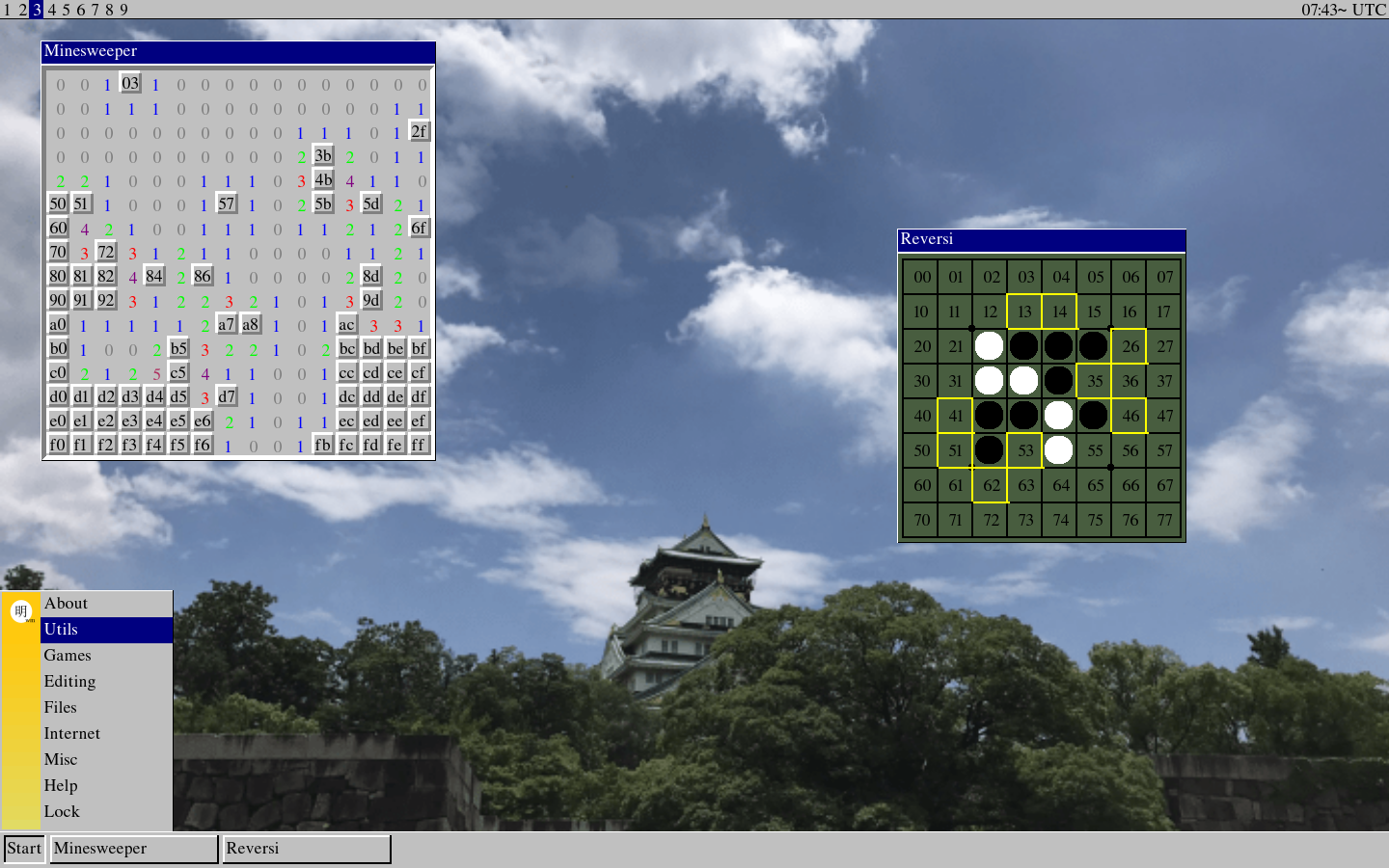

ming-wm is a window manager for Linux, that writes directly to framebuffer, instead of X windows or Wayland. It is 100% keyboard operated, and retro-themed. Documentation (including where the "philosophy" was originally "published" can be found here.

Ming-wm has two missions. In order of importance:

- Create an ideal desktop experience for me, the creator, and be fun to write code for

- Present an alternate vision (keyboard-based interfaces and an older aesthetic) to today's ugly and inefficient window managers

Mice are a local maximum - watch a power user of any application, and it's clear that the usage of keyboard shortcuts are a large part of what distinguishes them from everyone else. Mouse-based interfaces are definitely more intuitive, though there's some bias as nearly all mainstream applications of the last 30+ years have trained people to expect and understand them. But the reality is, no matter how familiar a person is with a mouse-based application, they can only move a mouse and click so fast. Typing on a keyboard will always be physically much faster who can competently type.

But are mice actually a local maximum? Could there not be some mythical interface that remains intuitive, but is just as powerful and fast as keyboard-based interfaces? Decades of multi-billion-dollar companies pouring countless engineer-, designer-, and scientist-hours have not invented or come close to inventing such an interface. This isn't a complex problem. It would be quite reasonable to believe no such interface exists.

And yes, there are some applications which are better off as mouse-operated than keyboard-operated: first person shooter games and apps such as Krita come to mind. Still, that is not to say it is not possible to practically make a first person shooter that is keyboard-operated; it just wouldn't be quite as efficient. Furthermore, these applications are a tiny minority. More applications than one might expect could absolutely become keyboard-based and blast the efficiency of the original out of the water; Inkscape comes to mind. Want real proof? the success of Vim (text editor), i3 (window manager), and Vimium (browser extension for controlling the browser) don't seem obvious or expected, but yet it is undeniable they are much better than any mouse-based counterparts.

Doesn't a mixed environment where the mouse and keyboard are equals seem the best of both worlds then? Yes, to some extent. There are three reasons ming-wm does not take that approach.

First, there is no real way to guarantee applications will fully support keyboard operation (in the unlikely event someone other than me makes a window for ming-wm) without making ming-wm keyboard only. That is, if mice were supported, applications may decide not to make themselves fully usable with only a keyboard. The only way to ensure applications treat the keyboard as a first-class citizen is to make that the only input method. This is a real threat. In the normal world of Linux where people use the X Window System or Wayland, a person can make the choice to use a keyboard-operated tiling WM like i3 or Sway, but there's really nothing to force the applications opened in that WM to support keyboard operation. Really, most applications can't be used with just a keyboard. Adjacent to the issue of applications possibly choosing not to fully support keyboard operation are users who, out of laziness, don't take advantage of the keyboard, choosing to use the more familiar mouse. Again, the only way to force users to learn the more efficient method of keyboard operation is to leave them no other choice. Imagine a world where everyone is a power user!

Second and more importantly, this window manager is first and foremost for my personal use and enjoyment. I know that I won't use a mouse. There really isn't a point to do double the work to support mice.

Thirdly, moving a mouse forces excessive screen redrawing. While that isn't an issue on any modern system, it still feels wasteful and goes against the Elm Architecture worshipped in ming-wm, which is discussed somewhere down below in its own section.

Local maximums are hard to move off of. They are maximums, after all. Moving off means, at least briefly, suffering productivity losses, confusion, and possibly frustration ("How do I exit vim??"). However, for anyone who uses a computer frequently, a relatively small one-time cost to learn some keyboard commands to permanently gain efficiency certainly seems worth it. Serious users already learn and use keyboard shortcuts, why not take the next logical step?

PS:

- Drawing applications are also not suited for keyboard operation, but neither are they suited for mouse operation. Those are best used with one of those fancy stylus things.

- Anecdotally, after two weeks of Vim (with no LSPs!), I was already faster and more productive than after years of Visual Studio Code. Disclaimer, I was by no means a Visual Studio Code power user or expert, but still.

- Ming-wm should not be confused as an elitist project. The point of the project is not for power-users to look down upon "normies". The focus on power-users is firstly because they are incredibly efficient (and therefore a sort of ideal to aspire to), and secondly because their habits align with the argument, proving it beyond me saying "trust me, this is true". As said in the main text, imagine if everyone was a power-user.

The design of today's websites, apps, and devices? Ugly, deceptive, corporate, soulless, boring, homogeneous, and devoid of meaning or beauty. New designs are pushed for the sake of newness and "modernisation". Those new designs not only rarely result in any real improvement, but more often than not are bundled with updates that actively degrade functionality. Some of this can be explained by "enshittification" (ie, trading quality for profit), but many are shockingly not driven by any profit motive.

In the past, design was a good proxy for quality. A "good" design meant that someone put in a decent amount of effort, and had some money. A "bad" (or lack of a) design meant the opposite. This is no longer true, because of how frequently this association is taken advantage of. Instead of real innovation, new designs are rolled out, creating the mere appearance of change. All the while, long requested features and bug fixes are neglected. Modern design is nothing but an exercise in fooling users. These farces aren't necessarily intentionally and maliciously plotted by evil corporations. The heuristic that "new and pretty = better" has so deeply penetrated our psyches that even the executives, product managers, and programmers perpuating that falsehood have "drunk their own Kool-Aid", so to speak. They truly do believe that putting lipstick on their dying pig is a good use of their resources. I beg them to feed it.

Of course, design is highly subjective. Is it right to call any design ugly and blan? Yes, yes it is. There are some objective measures of design, because design is part of a functional product, and functionality can be measured. A good designcan enhance functionality, discoverability, ease of use, etc. By this criteria, modern design admittedly does not always fail. But part of its success is because users have been trained to be accustomed to it. The elderly who have not had this exposure or training (a "control group"?) do not seem to think that modern design is particularly easy to use. People often dismiss the old as being too stubborn and resistant to change, and while that isn't entirely untrue, it seems too hasty to entirely dismiss their experience.

In contrast, designs of the ancient past (the 90s) had to quickly usable for those with little or no exposure to computer interfaces. At the same time, modern design of desktop interfaces is being influenced (read: dumbed-down) by how mobile interfaces work, losing functionality. So by measurable standards, modern design is a regression.

But how does this argument fit with ming-wm being keyboard-based? Aren't keyboard-based interfaces more unintuitive? Could a person with very little computer exposure really quickly understand keyboard-based interfaces? Indeed, this is a reasonable point. Telling grandma to write her e-mails in vim would not go well. However, there is an important difference between design and operation. Design and operation cannot be evaluated using the same criteria. The method of operation is not just essential, but is the product, the function, while design is a "nice-to-have". An apt analogy is food. It would be nice for food to look good (have a good design), but not strictly necessarily. On the other hand, the aesthetics of a food must not interfere with its taste or nutrition (function). The world's most beautiful dish will enjoy a trip to the trash if it tastes rotten and has negative nutritional value. Ming-wm achieves the best of both worlds: it looks good (by rejecting modern design), and tastes/functions great (by embracing keyboard-operation).

PS:

- Toddlers do seem to be able to get a good grasp of modern tech products. Then again, toddlers don't tend to use or understand any advanced features. And do we really want to rate designs is based on how toddlers can use it? Surely we can do better.

- In fact, rather than modern design no longer being a good indicator for high quality, I would argue that it is now a good indicator for low quality. I find that almost always, it is the shadiest companies and crypto-tokens that have the "sleekest" and most modern-looking websites. What they lack in sense and substance they are clearly compensating with fancy animations and mega-bytes of assets. This is especially now in the age of LLMs where any Dick or Jane can generate a swanky-looking website in thirty seconds, but also previously once CSS libraries like Bootstrap became common.

The Elm Architecture is an elegant and uncomplicated pattern named after the functional programming language Elm (used to create websites). In the Elm Architecture, components have a state, a view function (called draw in ming-wm) to turn that state into something that can be displayed (eg, HTML), and an update function (handle_message in ming-wm) that takes a message as input, and can choose to mutate the state.

Imagine there is a number input box. The state of the box would be the number it currently holds. The view function would draw the input box, with the number it holds inside. If the user presses a key on their keyboard while inside the input box, a message (that contains the key being pressed) is passed to the box's update function. If the key is a number, the box can update its state, and call for its view function to be run. If the key isn't a number, the box won't update its state, and doesn't need its view function to be run.

Restricting mutation of the state to the update function, and further defining how the state changes depending on what message is passed, makes code significantly cleaner and easier to reason about. The architecture is dead simple to understand and implement. More head space can be dedicated to the logic of a new feature, or figuring out what exactly causes a particular bug, rather than worrying about boilerplate, footguns, or other minutiae. The messages (which would typically be an enum) result in a complete definition of the functionality of an application, without having to go out of one's way. Having only one place where state changes happen makes it trivial to see, given a certain message, how the state is affected. In other models, one may need to run a search, perhaps even wading through several files to just find where the state of a component could be changed. As a side effect, it is incredibly easy to determine whether a redraw is necessary. If the state doesn't change, we know that there is no need to redraw!

Plus, with help from the Rust compiler, all applications can be forced to adhere to the architecture, and several classes of bugs can be caught at compile-time.

All of the above results not only in an exceptional developer experience and well defined functionality, but also allows any reader of the code to understand what is going on in as little time as possible.

PS:

- The number input box state should also account for it not holding any number (being empty), but assume it can never be empty - maybe it defaults to 0.

- Somewhat ironically, while the architecture is simple, explaining why and how it is so wonderful, in a way that gives it justice is not. The best way to understand is to try it out in a new project.

- Ming-wm does have a further belief that re-renders should only by initiated by user key-presses. One key-press can result in at most one re-render. This does mean videos or gifs won't be supported, but waste and unnecessary animations do not need to be worried about. Please note that without this belief, it would be fully possible for ming-wm to both support videos and use the Elm Architecture.

The term is usually used negatively, and fairly so. Business and research suffer with not-invented-here syndrome. Luckily, this is neither! Again, ming-wm is primarily for my own usage and enjoyment. I happen to enjoy not relying on dependencies, and writing as much as possible from scratch. In the minds of programmers, external packages are often black boxes. No one really reads the code of these libraries unless something is wrong (eg, some patch needs to be made, or the documentation is bad). All that time spent reading and understanding external code could probably be better spent writing it myself. I usually learn something new, and inherently have a better understanding of the project (it "fits in your head"). Of course, I'm not interested in rewriting everything from scratch, and I'm not qualified to do so anyways (eg, cryptography!). SerenityOS is another (much more impressive and large-scale) project that espouses this philosophy.

More often than not, not relying on dependencies removes unnecessary bloat and complexity (see the next "Simplicity / Rejection of Modern Design" section).

Expect to see more dependencies in Cargo.toml eliminated soon.

PS:

rodio is unlikely to ever be eliminated (simply because audio is complex), and it's optional (if the audio player is not wanted)bmp-rust is written by me and so isn't technically an external dependency

> [ming-wm](https://github.com/stjet/ming-wm) is a window manager for Linux, that writes directly to framebuffer, instead of X windows or Wayland. It is 100% keyboard operated, and retro-themed. Documentation (including where the "philosophy" was originally "published" can be found [here](https://github.com/stjet/ming-wm/tree/master/docs).

# Philosophy

Ming-wm has two missions. In order of importance:

1. Create an ideal desktop experience for me, the creator, and be fun to write code for

2. Present an alternate vision (keyboard-based interfaces and an older aesthetic) to today's ugly and inefficient window managers

## Keyboard-Only

Mice are a local maximum - watch a power user of any application, and it's clear that the usage of keyboard shortcuts are a large part of what distinguishes them from everyone else. Mouse-based interfaces are definitely more intuitive, though there's some bias as nearly all mainstream applications of the last 30+ years have trained people to expect and understand them. But the reality is, no matter how familiar a person is with a mouse-based application, they can only move a mouse and click so fast. Typing on a keyboard will always be physically much faster who can competently type.

But are mice *actually* a local maximum? Could there not be some mythical interface that remains intuitive, but is just as powerful and fast as keyboard-based interfaces? Decades of multi-billion-dollar companies pouring countless engineer-, designer-, and scientist-hours have not invented or come close to inventing such an interface. This isn't a complex problem. It would be quite reasonable to believe no such interface exists.

And yes, there are some applications which *are* better off as mouse-operated than keyboard-operated: first person shooter games and apps such as Krita come to mind. Still, that is not to say it is not possible to practically make a first person shooter that is keyboard-operated; it just wouldn't be quite as efficient. Furthermore, these applications are a tiny minority. More applications than one might expect could absolutely become keyboard-based and blast the efficiency of the original out of the water; Inkscape comes to mind. Want real proof? the success of Vim (text editor), i3 (window manager), and Vimium (browser extension for controlling the browser) don't seem obvious or expected, but yet it is undeniable they are much better than any mouse-based counterparts.

Doesn't a mixed environment where the mouse and keyboard are equals seem the best of both worlds then? Yes, to some extent. There are three reasons ming-wm does not take that approach.

First, there is no real way to guarantee applications will fully support keyboard operation (in the unlikely event someone other than me makes a window for ming-wm) without making ming-wm keyboard only. That is, if mice were supported, applications may decide not to make themselves fully usable with only a keyboard. The only way to ensure applications treat the keyboard as a first-class citizen is to make that the only input method. This is a real threat. In the normal world of Linux where people use the X Window System or Wayland, a person can make the choice to use a keyboard-operated tiling WM like i3 or Sway, but there's really nothing to force the applications opened in that WM to support keyboard operation. Really, most applications can't be used with just a keyboard. Adjacent to the issue of applications possibly choosing not to fully support keyboard operation are users who, out of laziness, don't take advantage of the keyboard, choosing to use the more familiar mouse. Again, the only way to force users to learn the more efficient method of keyboard operation is to leave them no other choice. Imagine a world where *everyone* is a power user!

Second and more importantly, this window manager is first and foremost for my personal use and enjoyment. I know that I won't use a mouse. There really isn't a point to do double the work to support mice.

Thirdly, moving a mouse forces excessive screen redrawing. While that isn't an issue on any modern system, it still feels wasteful and goes against the Elm Architecture worshipped in ming-wm, which is discussed somewhere down below in its own section.

Local maximums are hard to move off of. They are maximums, after all. Moving off means, at least briefly, suffering productivity losses, confusion, and possibly frustration ("How do I exit vim??"). However, for anyone who uses a computer frequently, a relatively small one-time cost to learn some keyboard commands to permanently gain efficiency certainly seems worth it. Serious users already learn and use keyboard shortcuts, why not take the next logical step?

PS:

1. Drawing applications are also not suited for keyboard operation, but neither are they suited for mouse operation. Those are best used with one of those fancy stylus things.

2. Anecdotally, after two weeks of Vim (with no LSPs!), I was already faster and more productive than after years of Visual Studio Code. Disclaimer, I was by no means a Visual Studio Code power user or expert, but still.

3. Ming-wm should not be confused as an elitist project. The point of the project is not for power-users to look down upon "normies". The focus on power-users is firstly because they are incredibly efficient (and therefore a sort of ideal to aspire to), and secondly because their habits align with the argument, proving it beyond me saying "trust me, this is true". As said in the main text, imagine if *everyone* was a power-user.

## Simplicity / Rejection of Modern (Tech) Design

The design of today's websites, apps, and devices? Ugly, deceptive, corporate, soulless, boring, homogeneous, and devoid of meaning or beauty. New designs are pushed for the sake of newness and "modernisation". Those new designs not only rarely result in any real improvement, but more often than not are bundled with updates that **actively degrade functionality**. Some of this can be explained by "enshittification" (ie, trading quality for profit), but many are shockingly not driven by any profit motive.

In the past, design was a good proxy for quality. A "good" design meant that someone put in a decent amount of effort, and had some money. A "bad" (or lack of a) design meant the opposite. This is no longer true, because of how frequently this association is taken advantage of. Instead of real innovation, new designs are rolled out, creating the mere appearance of change. All the while, long requested features and bug fixes are neglected. Modern design is nothing but an exercise in fooling users. These farces aren't necessarily intentionally and maliciously plotted by evil corporations. The heuristic that "new and pretty = better" has so deeply penetrated our psyches that even the executives, product managers, and programmers perpuating that falsehood have "drunk their own Kool-Aid", so to speak. They truly do believe that putting lipstick on their dying pig is a good use of their resources. I beg them to feed it.

Of course, design is highly subjective. Is it right to call any design ugly and blan? Yes, yes it is. There are some objective measures of design, because design is part of a functional product, and functionality can be measured. A good designcan enhance functionality, discoverability, ease of use, etc. By this criteria, modern design admittedly does not always fail. But part of its success is because users have been trained to be accustomed to it. The elderly who have not had this exposure or training (a "control group"?) do not seem to think that modern design is particularly easy to use. People often dismiss the old as being too stubborn and resistant to change, and while that isn't entirely untrue, it seems too hasty to entirely dismiss their experience.

In contrast, designs of the ancient past (the 90s) *had* to quickly usable for those with little or no exposure to computer interfaces. At the same time, modern design of desktop interfaces is being influenced (read: dumbed-down) by how mobile interfaces work, losing functionality. So by measurable standards, modern design is a regression.

But how does this argument fit with ming-wm being keyboard-based? Aren't keyboard-based interfaces more unintuitive? Could a person with very little computer exposure really quickly understand keyboard-based interfaces? Indeed, this is a reasonable point. Telling grandma to write her e-mails in vim would not go well. However, there is an important difference between design and operation. Design and operation cannot be evaluated using the same criteria. The method of operation is not just essential, but *is* the product, the function, while design is a "nice-to-have". An apt analogy is food. It would be nice for food to look good (have a good design), but not strictly necessarily. On the other hand, the aesthetics of a food must not interfere with its taste or nutrition (function). The world's most beautiful dish will enjoy a trip to the trash if it tastes rotten and has negative nutritional value. Ming-wm achieves the best of both worlds: it looks good (by rejecting modern design), and tastes/functions great (by embracing keyboard-operation).

PS:

1. Toddlers do seem to be able to get a good grasp of modern tech products. Then again, toddlers don't tend to use or understand any advanced features. And do we really want to rate designs is based on how *toddlers* can use it? Surely we can do better.

2. In fact, rather than modern design no longer being a good indicator for high quality, I would argue that it is now a good indicator for low quality. I find that almost always, it is the shadiest companies and crypto-tokens that have the "sleekest" and most modern-looking websites. What they lack in sense and substance they are clearly compensating with fancy animations and mega-bytes of assets. This is especially now in the age of LLMs where any Dick or Jane can generate a swanky-looking website in thirty seconds, but also previously once CSS libraries like Bootstrap became common.

## Elm Architecture

The Elm Architecture is an elegant and uncomplicated pattern named after the functional programming language Elm (used to create websites). In the Elm Architecture, components have a state, a view function (called `draw` in ming-wm) to turn that state into something that can be displayed (eg, HTML), and an update function (`handle_message` in ming-wm) that takes a message as input, and can choose to mutate the state.

Imagine there is a number input box. The state of the box would be the number it currently holds. The view function would draw the input box, with the number it holds inside. If the user presses a key on their keyboard while inside the input box, a message (that contains the key being pressed) is passed to the box's update function. If the key is a number, the box can update its state, and call for its view function to be run. If the key isn't a number, the box won't update its state, and doesn't need its view function to be run.

Restricting mutation of the state to the update function, and further defining how the state changes depending on what message is passed, makes code significantly cleaner and easier to reason about. The architecture is dead simple to understand and implement. More head space can be dedicated to the logic of a new feature, or figuring out what exactly causes a particular bug, rather than worrying about boilerplate, footguns, or other minutiae. The messages (which would typically be an enum) result in a complete definition of the functionality of an application, without having to go out of one's way. Having only one place where state changes happen makes it trivial to see, given a certain message, how the state is affected. In other models, one may need to run a search, perhaps even wading through several files to just find where the state of a component could be changed. As a side effect, it is incredibly easy to determine whether a redraw is necessary. If the state doesn't change, we *know* that there is no need to redraw!

Plus, with help from the Rust compiler, all applications can be forced to adhere to the architecture, and several classes of bugs can be caught at compile-time.

All of the above results not only in an exceptional developer experience and well defined functionality, but also allows any reader of the code to understand what is going on in as little time as possible.

PS:

1. The number input box state should also account for it not holding any number (being empty), but assume it can never be empty - maybe it defaults to 0.

2. Somewhat ironically, while the architecture is simple, explaining why and how it is so wonderful, in a way that gives it justice is not. The best way to understand is to try it out in a new project.

3. Ming-wm does have a further belief that re-renders should only by initiated by user key-presses. One key-press can result in at most one re-render. This does mean videos or gifs won't be supported, but waste and unnecessary animations do not need to be worried about. Please note that without this belief, it would be fully possible for ming-wm to both support videos and use the Elm Architecture.

## Not Invented Here

The term is usually used negatively, and fairly so. Business and research suffer with not-invented-here syndrome. Luckily, this is neither! Again, ming-wm is primarily for my own usage and enjoyment. I happen to enjoy not relying on dependencies, and writing as much as possible from scratch. In the minds of programmers, external packages are often black boxes. No one really reads the code of these libraries unless something is wrong (eg, some patch needs to be made, or the documentation is bad). All that time spent reading and understanding external code could probably be better spent writing it myself. I usually learn something new, and inherently have a better understanding of the project (it "fits in your head"). Of course, I'm not interested in rewriting everything from scratch, and I'm not qualified to do so anyways (eg, cryptography!). SerenityOS is another (much more impressive and large-scale) project that espouses this philosophy.

More often than not, not relying on dependencies removes unnecessary bloat and complexity (see the next "Simplicity / Rejection of Modern Design" section).

Expect to see more dependencies in Cargo.toml eliminated soon.

PS:

1. `rodio` is unlikely to ever be eliminated (simply because audio is *complex*), and it's optional (if the audio player is not wanted)

2. `bmp-rust` is written by me and so isn't technically an external dependency